How Top Performers Progress Faster

Having been inundated by productivity advice over the years, recurring themes began to appear:

- Block out a period of time to work on a SINGLE task versus multitasking

- Work without distractions. Turn your phone to airplane mode, snooze slack messages, run website blockers, etc.

- In between tasks, take a refreshing break. Go for a walk. Stretch. Do something to take your mind off of work.

- Eat food that gives you energy rather than causes you to crash.

- Get regular exercise.

- Get about 8 hours of sleep or whatever amount leaves you rejuvenated and refreshed (do not want to create sleep anxiety!)

Accomplishing the above can produce significant increases in task efficiency and overall productivity. Celebrate it! However, one key ingredient is missing from the productivity pie: Prioritizing your day.

Despite consistently executing the productivity principles above, if you prioritize unimportant work, you will end up back at zero. You may be focusing on your Facebook presence when what you should be doing is upping your Podcast game. You may be focusing on ways to make your technical skills more efficient when what your customers require is a proactive customer experience.

While we cannot replicate the exact tactics or strategies others have used, as the timing and circumstances are unique to them, we can extract principles, identifying underlying patterns of behavior exhibited by successful people, seeing how they prioritize their tasks to achieve their goals, regardless of what field they are in.

Before diving into the tactical principles, lets begin with the foundation:

What Is Your Master Plan?

In 1997, music professor Gary McPherson sought to find the answer to why certain music students progress quickly while others don’t.

He took a look at 157 randomly selected children, following the children for a few weeks before they picked up their first instrument around age 7 through to high school graduation. McPherson then tracked their progress through interviews, biometric tests, and videotaped practice sessions.

After 9 months, a bell curve began to emerge, as it usually does, showing the extremes of some students progressing quickly versus some not progressing at all, with the vast majority somewhere in between.

What accounted for this difference? IQ? Nope. A sense of rhythm? Nope.

McPherson discovered the X factor was an answer to one simple question: “For how long do you think you’ll play your new instrument?”

Prying deeper beyond the children’s initial answers of “I dunno,” they finally gave him a solid answer which he seperated into 3 levels of commitment: Short/Medium/Long.

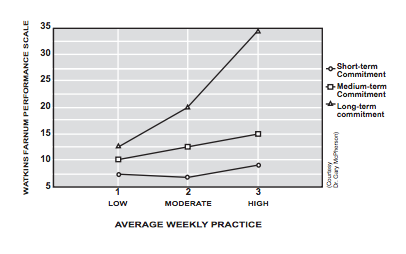

McPherson then measured how long each child practiced; low (20 minutes per week), medium (45 minutes per week), and high (90 minutes per week). The resulting graph looked like this:

With the same amount of practice, the long term-commitment group outperformed the short-term commitment group by 400 percent! The long-term-commitment group, with a mere twenty minutes of weekly practice, progressed faster than the short-termers who practiced for an hour and a half. When long-term commitment was combined with high levels of practice, skills skyrocketed.

For the long-term commitment group, at some point very early on, the children had a crystallizing experience that brought the idea to front of mind, that said, “I am a musician.” It became their identity.

If you are committed to something short term and you hit a bump in the road, you may be likely to quit. But if you are committed to the ‘big picture’ and are in it for the long haul, the bump in the road simply can become a learning experience; a signal to adjust one’s course and/or practice a little harder. Additionally, similar to how your brains Reticular Activating System (RAS) kicks into high gear when you notice all the Teslas on the road when you declare an interest in buying a Tesla, by adopting a long-term commitment, you start to notice things that can help you improve.

Two Additional Ways To Think About Long Term Commitments

Perhaps, like me, you cannot pinpoint a specific profession, such as a musician, that leads to a long term commitment.

For this dilemma, I turn to Ryan Holiday’s concept of “Grand Strategy” where he discusses Tyler Cowen, the bestselling author, economist, and thinker:

“Let’s say you wanted to become something like Tyler Cowen. Tactical hell would be thinking of ways to acquire what he possesses – getting a huge audience, bothering an editor at the New York Times Book Review, setting up a blog and trying to get linked by other important writers. It would be hell because you’d probably fail at each of these things. Grand strategy would be to think of what and why you want to be like Tyler. Perhaps, it’s that he’s paid to be curious or that you think you’d find fulfillment in the intellectually productive life he appears to lead. The separation of the person and the position leads to an understanding that latter flows from the former. The grand strategy is clear.”

Adding to this concept, Seth Godin writes:

What are you trying to build? What dent in the universe are you trying to make?

One additional way to think about it is, “Fix the lifestyle you want. Then work backwards from there,” as Cal Newport says:

Are you ultimately aiming for time-affluence? To play a meaningful role in the world of creativity or ideas? For adventure? For minimalism?

Knowing what you are trying to accomplish up front solves for numerous tactical decisions that follow. The fuzzier the target, the harder it is to hit.

---

(1) Have trouble choosing a vision? Watch this video by Neil Strauss & Ruth Chang